"I felt that I had a peculiar heritage in the Great Pyramid built...by the enterprising sons of Ham, from which I descended. The blood seemed to flow faster through my veins. I seemed to hear the echo of those illustrious Africans. I seemed to feel the impulse from those stirring characters who sent civilization to Greece...I felt lifted out of the commonplace grandeur of modern times; and, could my voice have reached every African in the world, I would have earnestly addressed him in the language of Hilary Teage--'Retake Your Fame!"

--Edward Wilmot Blyden, In the Great Pyramid of Khufu, July 11, 1866.

Tuesday morning as we entered the Great Pyramid of Khufu, we didn't engrave the

word "LIBERIA" at the entrance like the scholar and Pan Africanist Edward Wilmot

Blyden did on the occasion of his visit in July 1866. We didn't sing "O Isis and Osiris" from Mozart's The Magic Flute like Paul Robeson did when he stood in Khufu's burial chamber in 1938. We did, however, sing the Alma Mater as we climbed through the narrow passageways and, once inside the chamber, struck a resounding, pitch-perfect chorus of Lift Every Voice and Sing, ringing the granite sarcophagus and walls with the words and chords of the Johnson Brothers, James and Rosemond. Howard University has returned to the Nile Valley one year after our historic 2008 study abroad, and we had done so in force.

As we descended into the Pyramid, the rousing conversation that had carried well into t

he night the previous evening still echoed in

my ears. Having survived the long plane ride and emptied ourselves into the awaiting tour bus at the Cairo airport, our work had begun on Monday with a tour of the Mosque of Muhammad Ali Pasha at the Citadel, completed in 1848, a marker for the birth of the modern Egyptian state and a symbol of national pride. The irony was palpable: Here we were, entering our examination of the Nile Valley by touching base with the contemporary reality that modern Egypt is very different than ancient Egypt and at once still fortified and connected to the ancient ones in many lived, imagined and constructed ways.

Driving through the neighborhood of Heliopolis, we took note of the fact that this area had once been called On, and represented the home of the Kemetic symbol of intelligence, writing and memory, Djehuty (called Thoth by the Greeks and the symbol later borrowed and transmuted into Hermes and, later,Mercury). We will become well familiar with Djehuty and his female counterpart Seshat, the patron symbols of all thinkers and writers, over the course of our journey.

Finally, we arrived at the hotel, Le Meridien Pyramids, in the shadow of the largest pyramids in the country--and the world--those of Khufu, Khafre and Menkaure, as well as the Hor-em-Akhet (Heru of the Horizon), commonly known as the Great Sphinx of Giza. We

checked in, showered, ate dinner, and convened our first class session. Our band of 21 was tired but hardy, and we launched into a study abroad mbongi (a ki-kongo word for "room without walls," or "think tank"). Our initial theme--"The Politics of Translation"--proved ideally suited to the task of having us think about why we were in Kemet, where we found ourselves, and why it was so important for us to enter our study with questions of method and process attending our every step.

We began class by reintroducing ourse

lves to each other: in our intrepid band are Howard students in fields ranging from

History and Psychology to Communications, Africana Studies and Theater. We have been accompanied by an administrator from

Fisk University and her mother, as well as a scholar from Drexel University engaging in a study of African-American participation in study abroad initiatives. The Fiskite and her mother also happen to be my sister and mother (haha). The Drexel scholar also has deep Howard ties of blood and common purpose. For her eightieth birthday, my family chipped in and subsidized my mother's first trip to Africa. An Alabama Baptist, she had stood in the grand mosque and fell silent before the living witness of the common humanity of the heady mix of languages and cultures that surrounded us. Now she proclaimed herself the official tour "Grandmother," to the laughter of all.

With introductions and reasons for emptying blood and treasure into the cost of the trip re-stated and absorbed, we launched into our work. We immediately began to tease out the challenge of reading classical African history and culture through contemporary lenses, the challenge of translation. The work of discovery and recovery of ideas and experiences from the past is given astonishing force by the monumental work of the people of Kemet. The ancient Egyptians wrote on everything, it seems. Their language, Medew Netcher (literally "Divine Speech" or "Divine Words") was the foundation for the scripts we use today, though these have been reduced exclusively to markers for sound.

As our conversation entered its second hour, we were interrupted by the arrival of a small group of study tour participants from the U.S. led by my friend Manu Ampim, a scholar based in the Bay Area who has travelled to Kemet over twenty times. Later, we saw another colleague, Zizwe Poe, an Associate Professor of History at Lincoln University who is leading a study tour of the Nile Valley as well. I was reminded of the stories I heard from Asa Hilliard and Jacob Carruthers of running into colleagues and friends from the U.S. while examining the history and culture of Kemet. We were connected in so many ways, and Zizwe reminded me that Nnamdi Azikiwe, the First Prime Minister of independent Nigeria and a Lincoln University graduate, had actually started his undergraduate

work at Howard under William Leo Hansberry.

Azikiwe took the lessons on African history he learned from Hansberry to Lincoln, becoming the first person to offer a course on African history there.

We retired for the night after beginning to exchange the photographs and videos that will become part of this blog, allowing those following us at Howard and around the world to glimpse some of our real time reactions to what we are experiencing.

The next morning, we arose with the sun, grabbed a quick breakfast in the hotel dining room, and embarked for the Great Pyramid plateau of Giza, a bedrock site that looks down on modern Cairo and faces the south, Upper Kemet and Inner Africa. On a clear day--which, because of the pollution generated by twenty million city residents and workers occurs far too infrequently--a visitor to the Great Pyramid can look out over the expanse of desert and glimpse the first "true" pyramidal structures in the world, those constructed by Pharaoh Senefru and the workers of the fourth Kemetic dynasty (circa 2600 b.c.e.) at Meidum and Dashur. This was, needless to say, not a clear day. So we turned inward and journeyed to the burial chamber of the Great Pyramid of Pharaoh Khufu. Khufu, his grandson Khafre (whose pyramid we entered a bit later) and his great grandson Menkaure had their pyramids constructed in an alignment that mirrors the stars in Orion's belt. There are many theories about the plausibility of Kemetic attempts to literally mark the stars by placing pyramids and temples at strategic places up and down the Nile Valley, but there is no denying that these Africans had indeed charted the stars and aligned all of their major building projects with the rhythms of celestial and terrestrial phenomena.

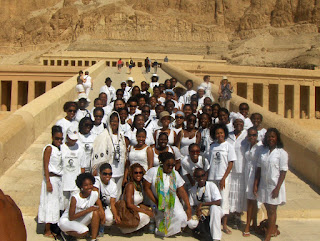

After we left the pyramid of Khafre, we scrutinized a funerary boat belonging to Khufu that has been perfectly preserved in a mini museum just outside the Great Pyramid. This boat, which dates at least to 2550 b.c.e., was recovered from the smallest of seven pits discovered so far by archeological teams. It is very small compared, for example, to the boat sent to Punt (modern day Somalia) by the Pharaoh Hatshepsut in 1480 b.c.e. In a few short days, we will visit Hatshepsut's temple, cut into the cliffs at Deir el-Bahri and site of the stirring photograph of the women members of the group that pioneered the Howard Summer Study Abroad in Kemet experience last year.

After leaving the Giza plateau, we stopped for lunch and to visit a shop for examining and purchasing shenew, the necklace form of

the ovals representing the universe that the Kemetians used to represent the names of the Pharaohs. These ovals were called "cartouches" by the French, and are a popular form of contemporary jewelry for visitors to the Nile Valley. Then it was off to the next major site: The Egyptian Museum.

The Egyptian Museum began its life as an idea initiated by the aforementioned Muhammad Ali in 1853. Ali realized that so many treasures from classical Africa were being looted by England, France, Germany, Italy and other European countries that an institution was necessary to restrict this cultural appropriation and keep Kemetic artifacts in the country. Five years later, a Bureau of Antiquities was established and in 1902, the building housing the current Egyptian Museum was completed. It is the largest collection of artifacts from a single country in the world.

We had prepped for our visit to the Egyptian Museum the night before in our initial meeting. We knew what we wanted and needed to see in order to ensure maximum benefit for the four hours we would be spending among the thousands of artifacts; highlights would include the Narmer Palate (the stone document chronicling the unification of Upper and Lower Kemet in 3100 b.c.e.), key statuary of Djoser, Khufu, Hatshepsut, Akhenaten and Nefertiti (and family), Amenhotep III and Tiye and, of course, the treasures of Tutankhamun. The central experience I could not wait to introduce our students to was a trip to the rooms that house several sakhu (mummies), including those of Seti I, Ramses II and Djehutymes III. These bodies have been preserved in such a striking fashion that those looking upon the visages of these long-deceased Pharaohs fall silent in wonder.

Before we entered the museum, we poured a libation outside the museum in respect for the ancestors. We'd performed a similar ritual at the same place the year before. Then, we entered the museum...WHOA! Look at the time! It's 5:45 a.m. here, and my luggage has to be outside my door at 6 a.m. in order to be loaded for the trip to Aswan! Okay, this post has to end. This is only a teaser: When we arrive, we'll pick up from here and continue to chronicle our first several days in Kemet. Today, we're going to visit Saqqara, the site of the first free standing stone building in world history, designed by Imhotep. We're also going to the tombs of Ptah Hotep and Kagemmi (brilliant authors of wisdom texts in the Old Kingdom) and Hwt-Ka-Ptah (house of the soul of Ptah), called "Memphis" by the Greeks and the place that provided the name "Egypt" from the Greek pronunciation "aigyptos." More later...gotta go put that bag outside my door! Stay tuned!

6 comments:

Dr. Carr, brother this is awesome. Thanks for continuing the seminal works of Drs. Ben, Clarke, Hilliard, Listervelt Middleton, Jefferies, etc.

Hotep

Alvin Cannon

The greatest education our students can experience is what you are giving them. It will launch them into any discipline they chose to specialize in. This is a sacred mission that will never be forgotten.

Kwaku Person-Lynn, Ph.D.

Greg and Dana, this blog is terrific! It will be a great resource long after you return. Hopefully, other HU faculty and students will try blogging after they see this masterpiece.

ENJOY!

Teresa

Thanks so much everyone! Alvin and Kwaku, you know we all continue to attempt to carry on the long tradition of the scholars and intellectual trailblazers who came before us. These young people share the enthusiasm and heartfelt commitment of these pioneers. Teresa, we feel the same way: blogging is an amazing experience! The ability to communicate and interact in real time is remarkable. More to come! Greg

I'm a bit behind, but I'll be catching up and spreading the word further. Great work! Hold it down!

Today it is generally recognized that Hatshepsut assumed the position of pharaoh and the length of her reign usually is given as twenty-two years, since she was assigned a reign of twenty-one years and nine months by the third-century B.C. historian, Manetho, who had access to many records that now are lost.

Egypt Hatshepsut Temple

Post a Comment